In Part 1: Naturally Re-thinking Manufacturing, we discussed increased demand for natural food and associated high barriers to scale. We then examined the divergent paths of food brands and manufacturing infrastructure in Part II: Diverging Brands and Manufacturers.

Perception in the food industry is that innovation is the only path to democratizing natural food. I partially agree. Innovation is the sparkplug of progress, but globalization is the engine. A loud, roaring start may impress crowds, but the engine must be large and efficient enough to travel far. The heat of the initial spark has little to do with how the engine performs at 60 mph on the highway. The engine’s efficiency is determined by the rate of fuel it utilizes to reach its goal: distance over time (velocity). To stick with our car analogy, premium natural food brands are like sports cars – they are impressive and beautiful – art and utility intertwined. Sports cars are expensive, though, and everyone wants to drive. So, we need Toyota Camrys (or whatever – don’t send me emails about cars). Private label used to be the Yugo of the food world: cheap, but “gets me from A to B.” Now it’s becoming CPG’s Camry: reliable, consistent, and genuinely has the attributes consumers want.

History shows that consumers will not pay up for more innovation in food (more on that later). American household income has grown steadily since WWII but expenditures on packaged foods fail to keep up. Food is a staple, but when people upgrade their lifestyles, they don’t materially increase their spending on packaged goods. The mass market will shift its spending habits but will not incrementally increase them in pace with either innovation or income. Thus, packaged food must always trend toward commoditization (see Diverging Brands & Manufacturers for more on this):

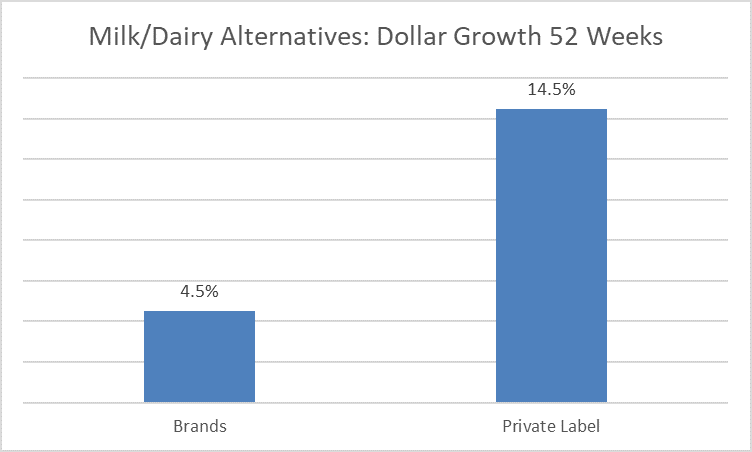

Commoditization does not mean innovation goes away. It means that competition globalizes supply and margin is competed away. What was once innovation becomes widely available and inexpensive. For example, almond milk was once expensive and available only under the Blue Diamond brand. Then Silk entered the space. Then hundreds of smaller niche brands offering macadamia milk, cold-pressed nut milks, and nut milks enhanced with pea protein isolate. Then every conventional grocer had their own brand. Extended shelf life producers like Stremmick’s Heritage Foods built billion dollar businesses around making the product for the underlying brands and ultimately became the crux for the entire category. Now, in the past 52 weeks, private label milk & dairy alternatives (read: plant-based milk, cheese, and yogurt) are growing more 3x as fast brands[1]:

Is this phenomenon unique to plant-based milks? No. Private label is emerging quickly and eating up margin. I believe this is evidence of the “commoditization” of natural food.

Private Label is Eating the Food Industry

First thing’s first. When we say “private label,” we mean store brands. These are products that grocery stores pay manufacturers to make for them. Sometimes people use the term private label in place of “contract manufacturing,” which broadly refers to manufacturing being offered as a service, but this section refers to store brands.

Store brands allow retailers to “cut out the middle man” and put products on shelf without sourcing from a brand, who often sources from the same manufacturer. We are finding that consumers are increasingly brand agnostic and attribute focused. It has long been thought that brands bring innovation that private label eventually copies. The line is starting to blur, and the blurrier it gets, the more affordable premium foods are.

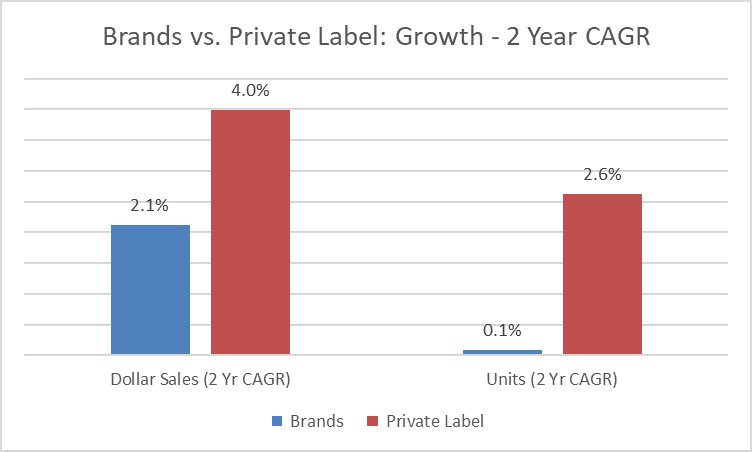

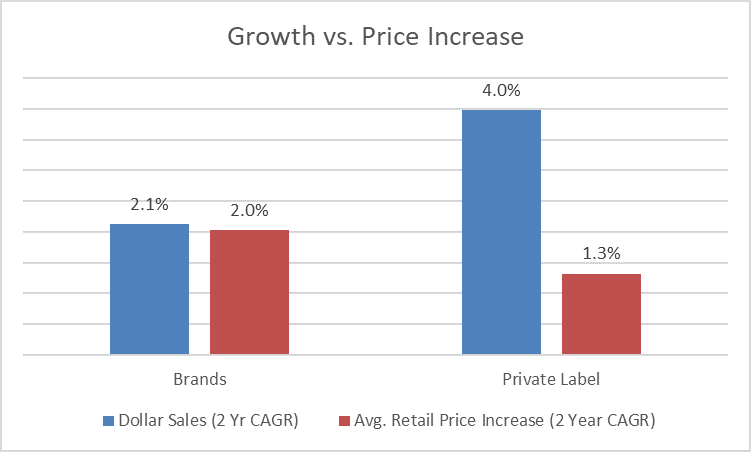

According to Nielsen,[2] private label prices are climbing, but they still offer an average discount of 4.4%. Furthermore, store brands are growing at nearly twice the clip of brands:

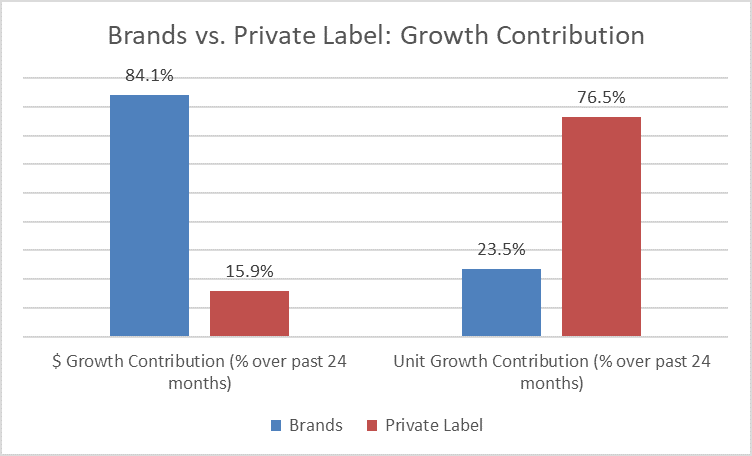

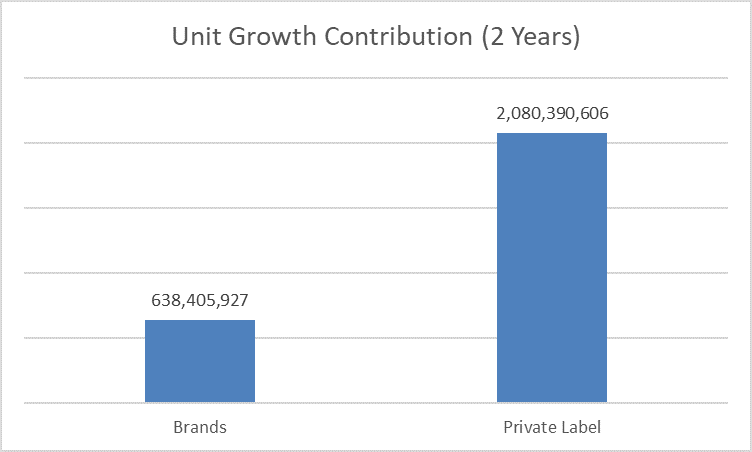

Is private label large enough to matter? Yes. While brands contributed 84.1% of dollar growth, private label actual contributed nearly three quarters of all unit growth in the past 2 years:

How can this be so? The inversion in the chart above implies that two things are happening: (1) private label is taking unit share away from brands, and (2) since unit growth is positive overall, incremental consumers are still entering the category. Private label is contributing nearly 3x as many incremental unit sales to the market than brands:

Meanwhile, nearly all the branded growth is coming from price increases. Private label has been increasing prices too, but its growth is coming from incremental unit sales:

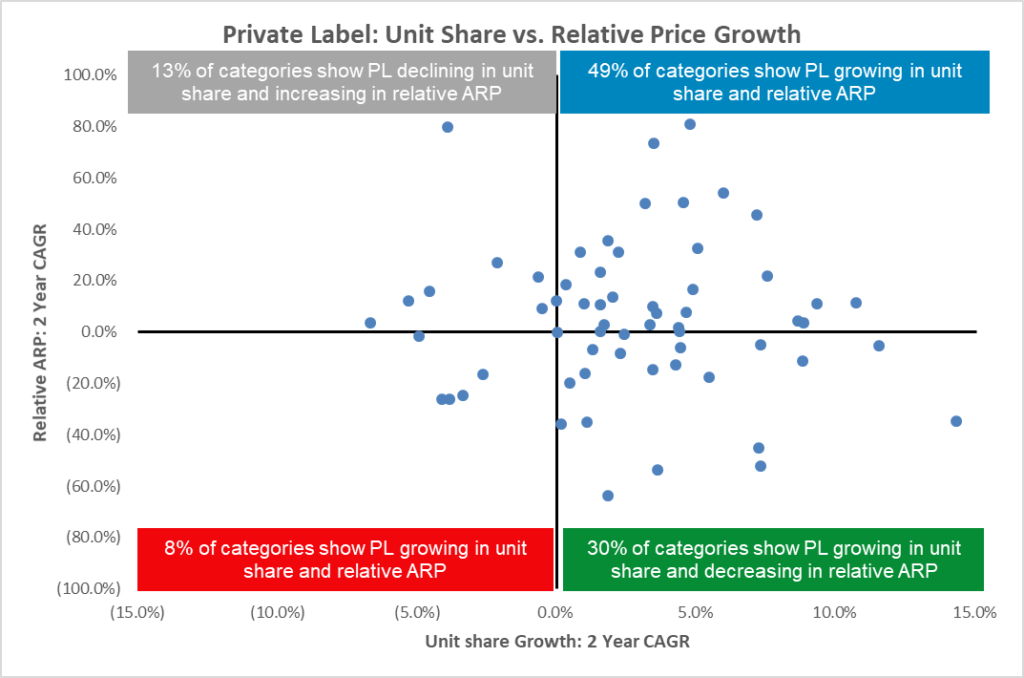

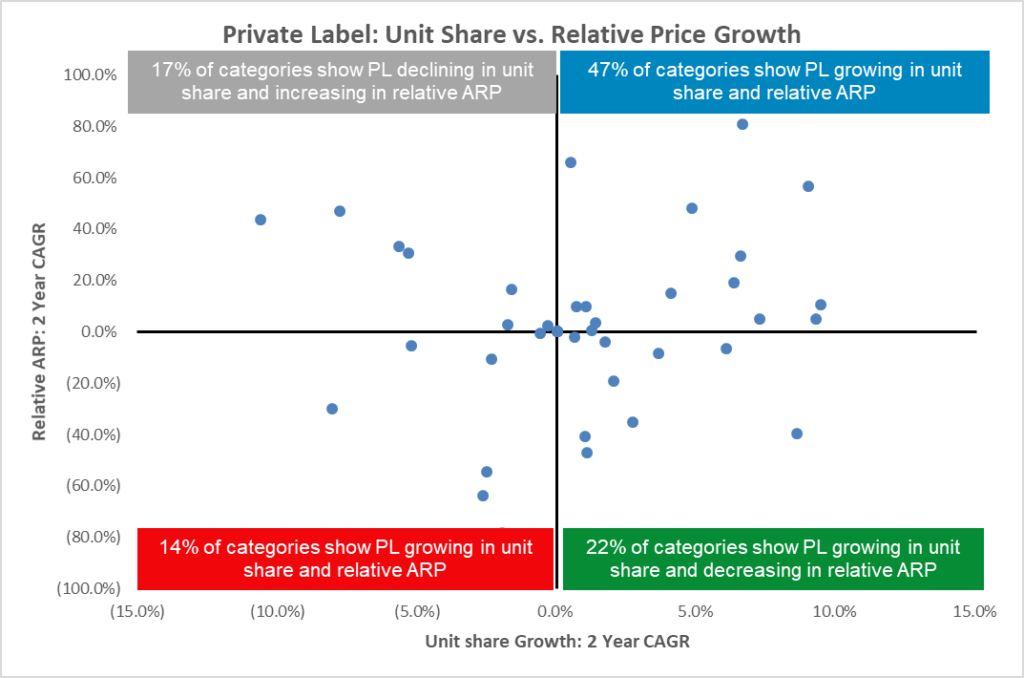

All of this begs the question: is private label adding value or detracting? Are people still buying natural/organic foods or are they buying Kroger brand baked beans instead? If private label is increasing unit share in categories by simply stripping out price, then perhaps it is eating value. In fact, the opposite is true. Private label is both eating market share and increasing its price points relative to national brands. It appears to be enjoying the perceived value with consumers while maintaining a safe distance from national brands via discount. We compared the change in average retail price (ARP) of private label goods to brands by category. Then, we compared unit share by category for private label. Here is what we found:

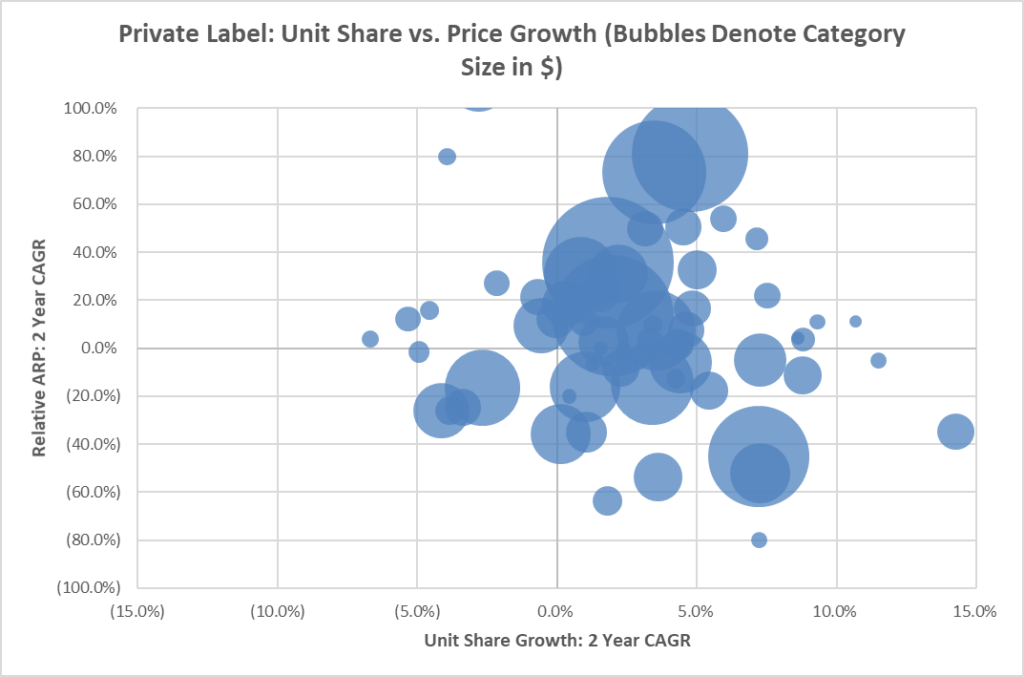

An alarming 79% of the 79 Nielsen super-categories we measured are seeing private label grow in unit share. Furthermore, 62% are seeing price increases relative to the overall category. In other words, private label is eating market share and increasing prices faster than national brands. This suggests incredible competitive strength on the part of store brands. Is this phenomenon limited to small categories? On the contrary. The chart below shows this phenomenon occurring in large categories:

What About Whole Foods Market (WFM)?

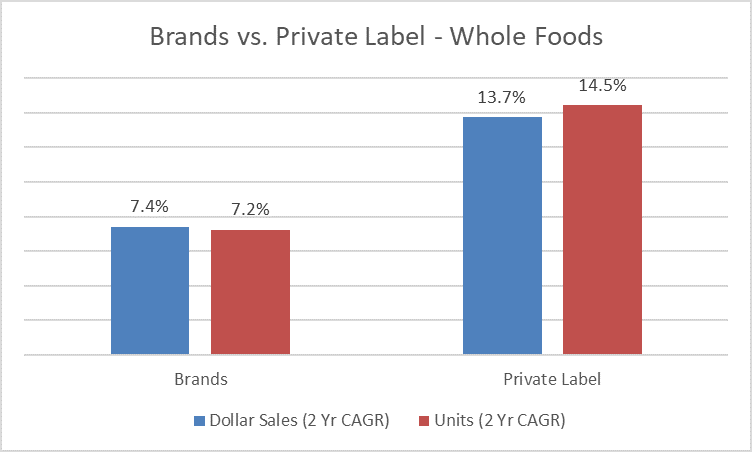

It’s easy to imagine private label taking over in mainstream grocery, but what about the famed “Whole Paycheck?” The trends are the same: private label is growing twice as fast:

And at the category level, WFM is taking price with its own brands and enjoying share increase:

Will Private Label Slow Down?

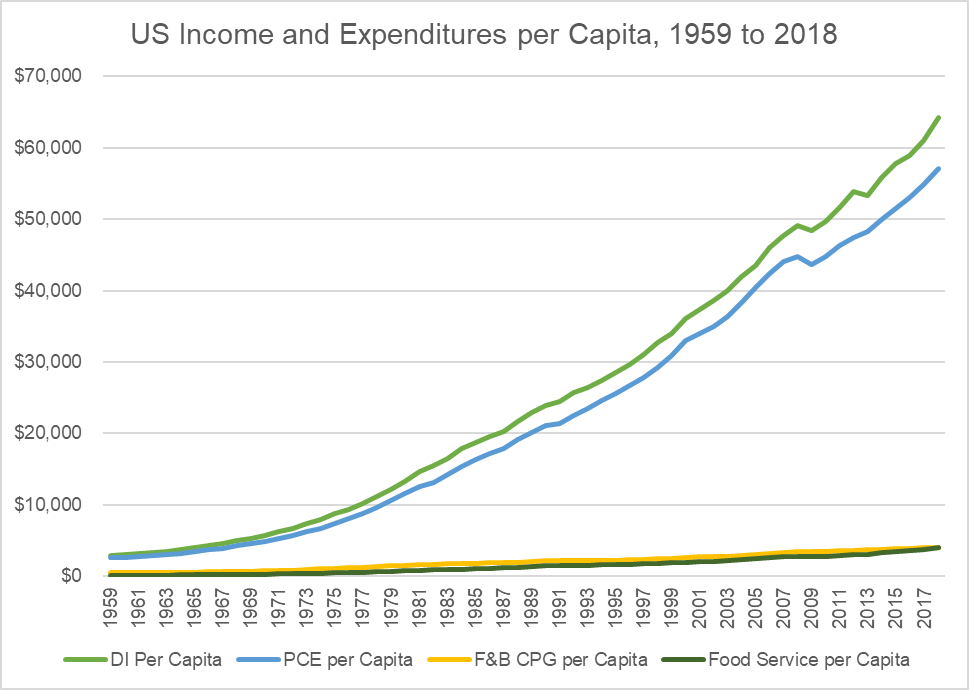

Directionally? Sure. The growth rates are not sustainable, but it will likely continue to eat share in natural food. It is the most obvious way for natural food to be democratized in an environment where people pinch pennies. As mentioned above, no matter how wealthy Americans get, they don’t increase their CPG spend. Let’s look at the evidence: how we earn and spend (note: all of the following data is directly pulled from the Bureau of Economic Analysis website).

The economic enablers of food & beverage consumption are (1) disposable income (DI) and (2) personal consumption expenditures (PCE). DI is what you earn from wages and salaries and other sources of income less what you pay to the government for social benefits (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, etc.) less your taxes. Your DI less the cash you save or pay out in interest (e.g.: mortgage) is your PCE. PCE is generally divided into durable goods (e.g.: automobiles and parts, home furnishings, recreational goods), non-durable goods (e.g.: off-premise food & beverage, clothing, gas, personal care products), and services (e.g.: rent, healthcare, transportation, recreation, food service, insurance, etc.).

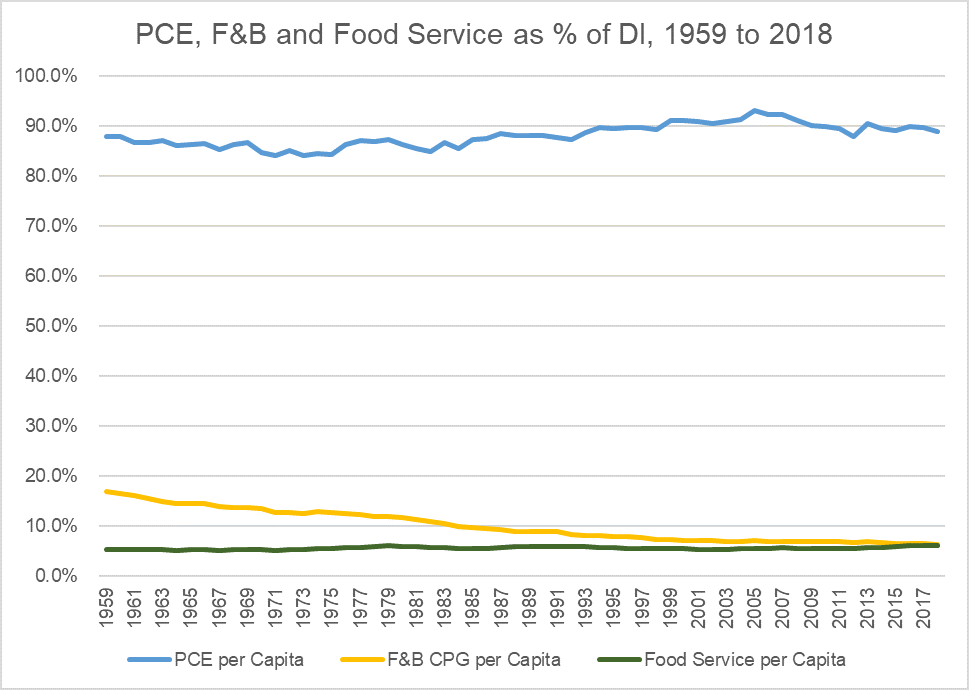

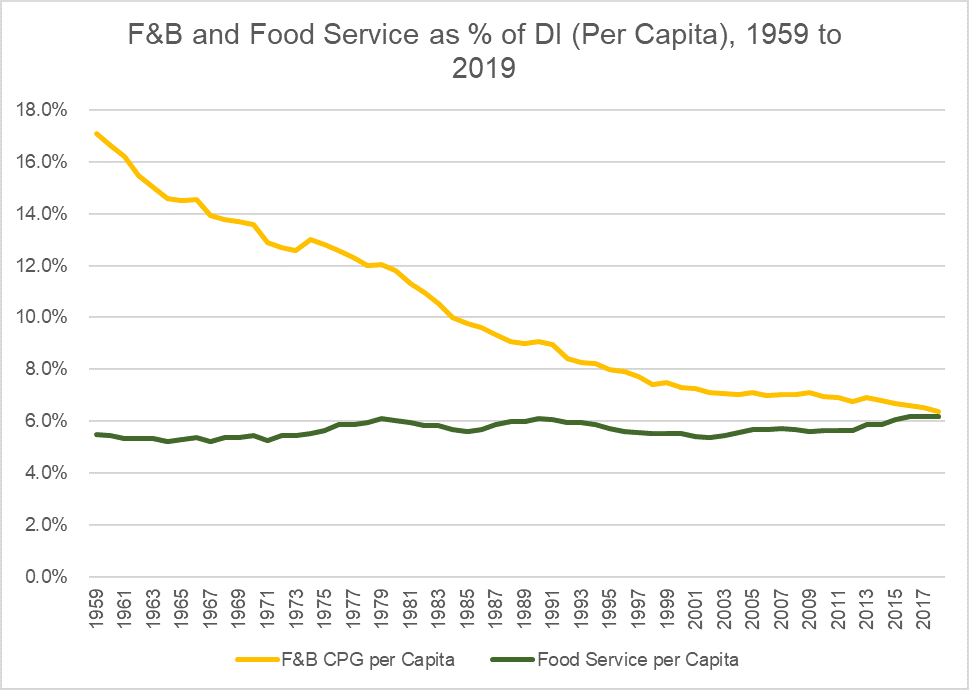

First, notice that American per capita DI has grown steadily along with PCE. This means that as Americans make more money, they consume proportionately more. These upgrades come in durable goods and services, however. Not packaged food. They do not spend more on packaged food and drink. Going forward, we’ll divide food and drink into two categories: (1) off-premise food and beverage, which means packaged food and beverage not purchased on the premises of a restaurant (“F&B CPG”), and (2) food service, or food and drink purchased on the premises of a restaurant (“Food Service”). Note: the charts below are not inflation adjusted to show in absolute terms that people do not increase their spending in accord with income.

Look even more closely: PCE has hovered at approximately 88% of DI forever. Meanwhile, F&B CPG has actually declined significantly while Food Service has grown modestly.

In fact, it may be that Americans will soon be eating out more than eating in. Lots of other articles discuss drivers for these demographics (urbanization, declining birthrates, mobile work-lives, etc.).

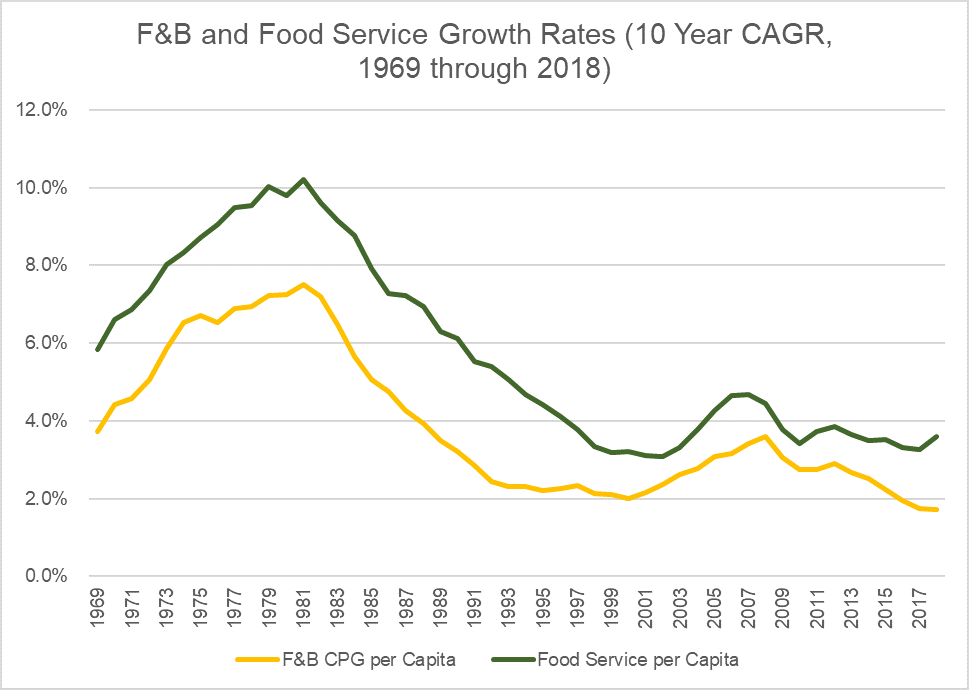

If we “smooth” out the data a bit by looking at 10-year compound growth rates, we can see that Food Service has always outgrown food, but the rate of its growth is actually declining too.

Conclusion

It is clearly a losing strategy to bet on increased CPG spend per capita by Americans, regardless of economic cycle. Thus, the price per unit per capita matters. That said, trends obviously suggest that we’ll upgrade to better, cleaner food when we can. These trends showing up in the lower-cost world of private label makes intuitive sense.

Remember the chart that showed all of brand growth coming from price increases? If premiumization is your long-term price strategy, steady food & beverage consumer wallet share decline over 50 years, might be a little jarring. This puts immense pressure on brands to innovate. If the Innovation Cycle reaches commoditization, they must pivot somehow. The result is either stratification of the category or innovation into new categories.

A third option could exist as well: control over your supply chain and tacit knowledge around making the product. Every extended shelf life producer in the world knows how to make almond milk. But what if that process was closely held by Blue Diamond for longer? I acknowledge that I’m just pipe-dreaming – an almond co-op could never build the manufacturing infrastructure required to do this, but perhaps we’d be calling almond milk “Blue Diamond Milk” even today if it were possible. We could be entering a part of the cycle where scale and price really matter, tipping the advantage toward those who control the ability to globalize innovation.

If the growth continues to careen toward private label, the advantage lies in the hands of those who can supply the store brands. The CPG business model over the past 10 years involved pairing sales & marketing with innovation. In a private label friendly environment, the next 10 years will witness innovation paired with manufacturing and supply chain execution.

[1] Nielsen xAOC data as of 8/10/19 [2] Nielsen xAOC data as of 8/10/19 for 71 super-categories in food and pet food.